In recent years, cold spray process is increasingly used for additive manufacturing of metallic components, re- ferred to as cold spray additive manufacturing (CSAM). Unlike the fusion-based AM processes, CSAM is achieved in a solid-state, bringing several advantages such as the absence of severe oxidation or phase composition changes. At the moment, the main limitation of CSAM is the generally low ductility of the as-sprayed deposits. In this paper, using Cu as a model material, we demonstrate a way to overcome this limitation. Importantly, a high ductility of the deposits in their as-sprayed state is achieved without a trade-o? in mechanical strength. Furthermore, we show that without any post-heat treatment, the properties of CSAM Cu are comparable to bulk, non-AM Cu.

1. Introduction

Lately, cold spray technology (CS) is gradually recognized as a new additive manufacturing (AM) technique. In the cold spray process, micron-sized powder particles are accelerated by a propelling gas fed through a de Laval nozzle. The particles then impact onto the man- drel/substrate at supersonic velocities and undergo extensive plastic de- formation, creating a ?rm bond with the underlying material[1–3]. Cold spray o?ers short production times, great process economy, virtually unlimited component size capability, and ?exibility for a localized de- position. Given these, the CS process actually o?ers unique advantages over the AM techniques where thermal energy is the main principle of deposition (selective laser melting, electron beam melting, laser engi- neered net shaping and laser metal deposition) [4, 5]. Moreover, since the CSAM is done in a solid state, the production of metallic parts is without severe oxidation or phase changes [6, 7], and importantly, CS is more suited for AM of high re?ectivity metals (such as Cu) that are problematic to process using the laser-assisted AM processes [8].

The cold spray process is now a well-established technique for metal- lic deposits in various industries. It has been used to produce protective or performance enhancing coatings, as well as near net shapes [9]. Aside from these, CS has also been proven to be a cost-e?ective process for re- pair and restoration of damaged aerospace components (in[10], a repair of Seahawk helicopter modules using CS is presented, leading to savings as high as 35–50% of a new component manufacture price).

powder particles are accelerated by a propelling gas fed through a de Laval nozzle. The particles then impact onto the man- drel/substrate at supersonic velocities and undergo extensive plastic de- formation, creating a ?rm bond with the underlying material[1–3]. Cold spray o?ers short production times, great process economy, virtually unlimited component size capability, and ?exibility for a localized de- position. Given these, the CS process actually o?ers unique advantages over the AM techniques where thermal energy is the main principle of deposition (selective laser melting, electron beam melting, laser engi- neered net shaping and laser metal deposition) [4, 5]. Moreover, since the CSAM is done in a solid state, the production of metallic parts is without severe oxidation or phase changes [6, 7], and importantly, CS is more suited for AM of high re?ectivity metals (such as Cu) that are problematic to process using the laser-assisted AM processes [8].

The cold spray process is now a well-established technique for metal- lic deposits in various industries. It has been used to produce protective or performance enhancing coatings, as well as near net shapes [9]. Aside from these, CS has also been proven to be a cost-e?ective process for re- pair and restoration of damaged aerospace components (in[10], a repair of Seahawk helicopter modules using CS is presented, leading to savings as high as 35–50% of a new component manufacture price).

At the moment, the main limitation of the cold spray process is the extremely low ductility of the deposits, an attribute arising from the se- vere plastic deformation of the powder particles and the associated cold work hardening phenomenon. To restore the ductility, CSAM materi- als are often subjected to a heat treatment to induce recrystallization and consolidation [11]. This high mechanical strength with almost zero ductility in the as-sprayed state and a subsequent ductility enhance- ment by post-heat treatment was reported by several researchers. For instance, Meng et al. [12] observed less than 1% elongation in the cold sprayed 304 stainless steel, which was enhanced 5× after heat treat- ment. In the case of Inconel 718, it has been observed that elongation in the as-sprayed material was only 0.5%, which increased 8–10x after annealing [13–15]. Yu etal. (2019) also observed the high mechanical strength and poor ductility with almost no elongation in the case of Cu, which, yet again, improved by heat treatment [16]. Yin et al. (2018) reported ~ 2.5% elongation in the as-sprayed state of cold sprayed Cu, which was improved by 7.6% after annealing at 500 °C for 4 h [17].

The presented study demonstrates a method to overcome this prob- lem. Our Cu deposits exhibited high ductility in the as-sprayed state without any heat treatment. Importantly, this was achieved without any signi?cant trade-o? with regard to their mechanical strength and using cheaper nitrogen as a process gas (no helium needed). In this paper, the in?uence of powder particle sizes and process parameters on microstruc- tural and mechanical properties is presented, and the properties of our CSAM Cu in the as-sprayed state are further compared with bulk Cu.

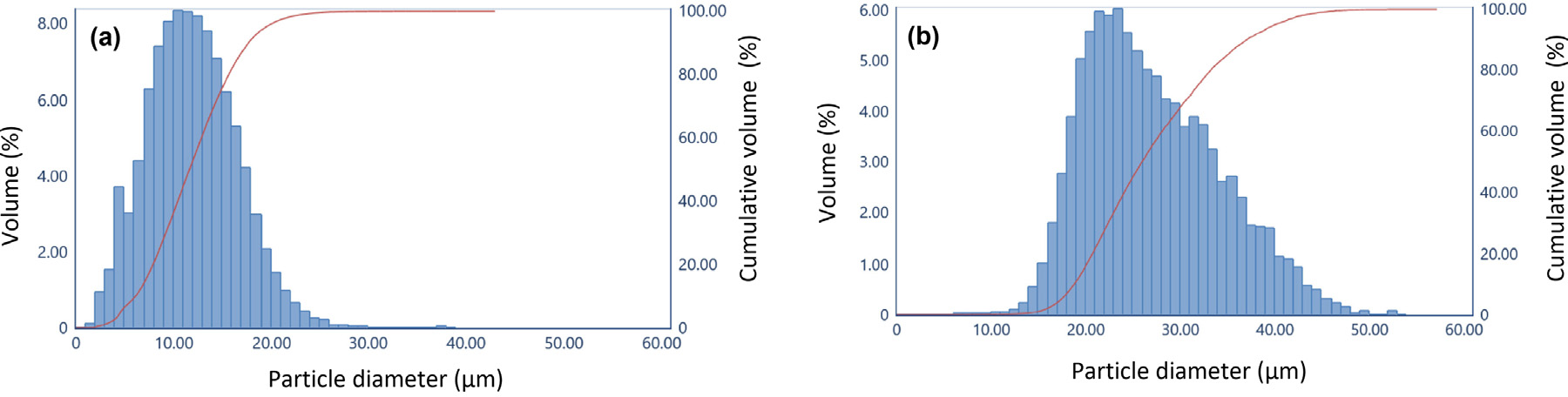

Fig. 1. Particle size distribution of the used (a) ?ne and (b) coarse Cu powders.

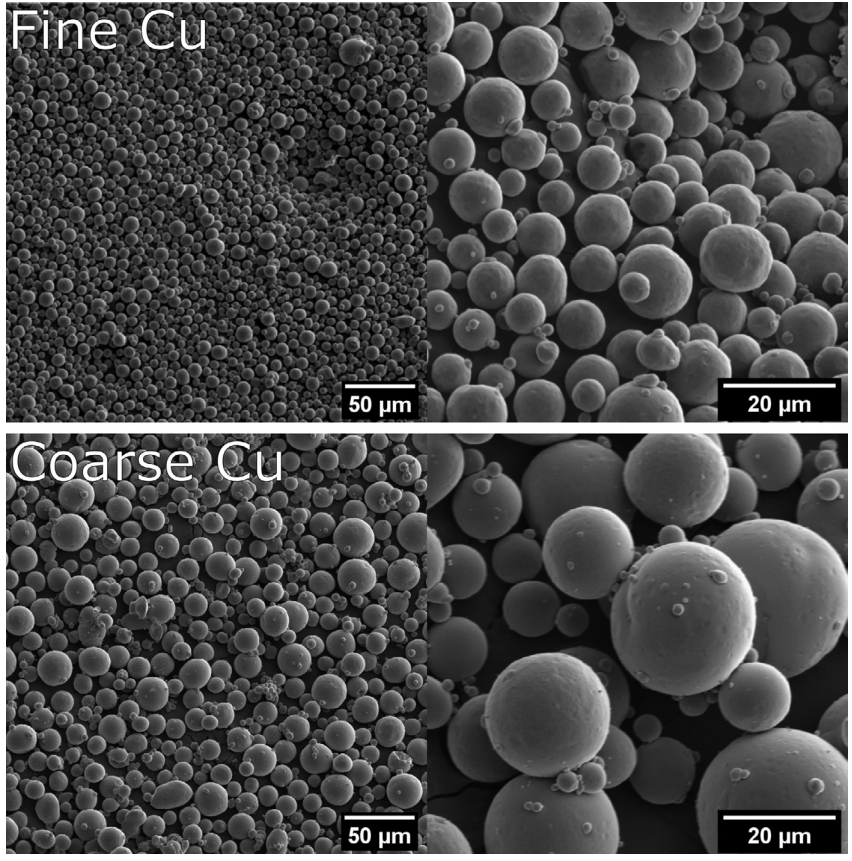

Table 1

Deposition process parameters.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Powder feedstock

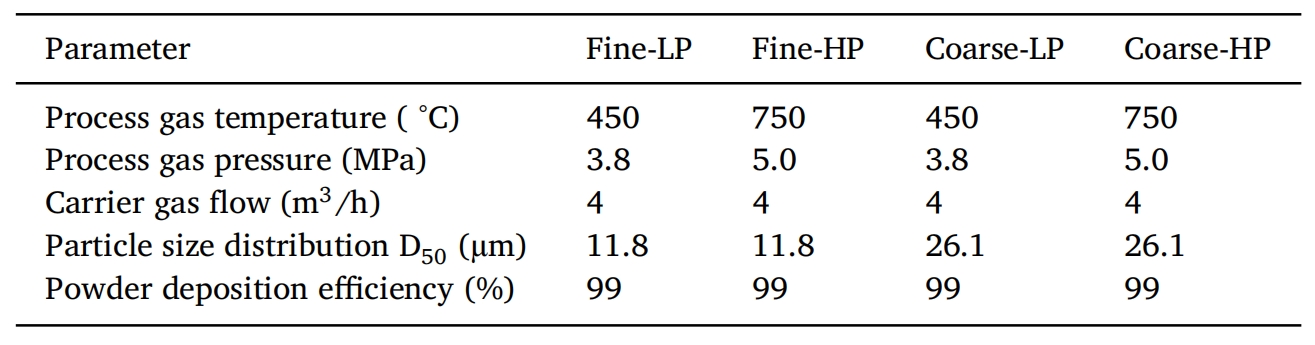

Two high purity Cu powders (99.95%, Impact Innovations GmbH) with di?erent particle size distributions were used to demonstrate the discovered principle (Fig. 1). The atomized powders had a spher- ical morphology, shown in Figure 22 for the ?ne powder with D10 = 6.2 μm, D50 = 11.8 μm, D90 = 17.8 μm and the coarse powder with D10 = 18.9 μm D50 = 26.1 μm, D90 = 40 μm.

2.2. Deposition process

Impact Innovations ISS 5/8 high-pressure gun with central injection system and OUT 1 nozzle (expansion ratio 5.6) was used for the de- position. Nitrogen was used as a propellant and feedstock carrier gas. Combining two feedstock powders (?ne, coarse) and two proposed sets of process parameters (low - LP, high – HP, Table 1), four sample sets were prepared. The values of parameters for LP and HP were obtained in a preliminary in-house study. For all four depositions, a gun traverse speed of 500 mm/s, a stand-o? distance of 30 mm, and a raster step size of 1 mm were used. The deposition parameters matrix is provided in Table 1. For each set, two aluminum plates of 70 × 70 mm2 dimensions were used as substrates for deposition of 5–6 mm thick Cu coatings. Af- ter the deposition, the plates were removed to obtain free-standing Cu deposits. No additional heat treatment was performed.

To help understand the underlying principles, the in-?ight velocity of the powder particles was measured by CSM EVOLUTION cold spray meter (Tecnar Automation Inc., Canada) equipped with a continuous diode laser source to illuminate the particle plume (790 nm wavelength, 3.3 W power, 70 mrad divergence).

2.3. Sample characterization

Metallographic samples were prepared from the deposits using stan- dard procedures with the ?nal polishing realized using a 1-μm dia- mond paste. The sample cross-sections were analyzed using EVO MA 15 scanning electron microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). The microstruc- tural analysis was extended by advanced electron backscatter di?raction (EBSD) mapping using FEG/SEM Zeiss Ultra Plus (Carl Zeiss, Germany) equipped with HKL Nordlys EBSD detector (Oxford Instruments, UK). The EBSD data sets were acquired at an acceleration voltage of 20 kV with a 120 μm aperture in high/current mode using Aztech software (Oxford Instruments, UK). The acquisition step size was 200 nm, and the camera binning was adapted to reliable pattern recognition (4 × 4, in this case).

The compactness of the samples was assessed through a gas tightness test using a helium-leak detector (Qualytest HTL 260, Pfei?er Vacuum GmbH,Asslar, Germany) in IEK-1, Forschungszentrum Jülich, Germany. A ?ow of He was maintained at one side of the deposits, while a vacuum was drawn on their other side. The amount of He leaking through the samples was recorded.

For mechanical properties testing, a tensile test and hardness mea- surement were selected. For the former, ?at specimens (having a length of 60 mm) were EDM-cut out of the free-standing Cu deposits and the test was performed using a conventional tensile rig according to the EN ISO 6892–1 standard, except that the suggested mechanical extensome- ter was replaced with a virtual digital image correlation (DIC) exten- someter. This setup has previously been assessed as an e?ective way for material characterization [18,19] and it was shown that the contactless extensometer yields results fully comparable to those acquired by the mechanical extensometer. Using the virtual extensometer has another advantage, minimizing the probability of crack initiation due to sample surface scratching by the extensometer knife. A tensile load was applied at a constant rate of 0.4 mm/min until the fracture and the material’s stress response was recorded. The hardness of the deposits was measured by the Vickers method using Q10A+ (Qness, Austria). Considering the grain sizes and microstructure features, a load of 300 gf was selected (HV0.3 ) for all samples. The measurements were carried out following the ISO 6507–1 standard (spacing of indents at least 3× the indent size). Twenty indentations were used to calculate the average value of each sample. A two-tailed unpaired t-test was used to determine the statis- tical signi?cance between hardness of deposits produced at LP and HP for both ?ne and coarse powders. The used level of signi?cance was *p = 0.01.

Thermal conductivity λ of the samples was calculated based on the measurements of thermal di?usivity a, density P, and heat capacity cp according to the formula λ = a × P × cp. The measurement of thermal di?usivity was performed by a laser ?ash method in a vacuum using the LFA 1000 tester (Linseis, Germany). To ensure uniform absorption of the laser pulse and equal radiation properties of the surfaces, the 10 × 10 × 2 mm3 samples were coated with a thin layer of graphite. For all samples, ?ve measurements were taken at every temperature from 20 to 800 °C. The density P of the samples was measured using the Archimedes method (immersion of samples in water) and its respective temperature dependence was calculated based on the density tempera- ture dependence of pure bulk Cu. For the calculations, the heat capacity cp of pure copper was used.

The obtained properties measured by various methods were com- pared against bulk Cu material. To avoid incorporation of potential sec- ondary in?uences and maintain a full mutual comparability, the Cu bulk was an identical material from which the two powders used here were atomized.

Fig. 2. Spherical morphology of the used ?ne and coarse Cu powders.

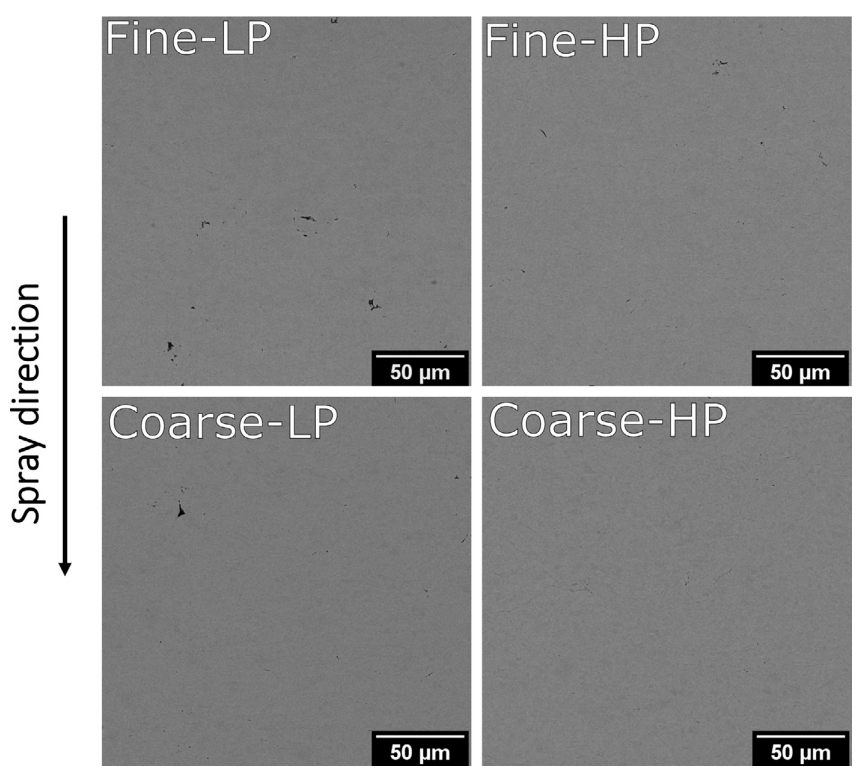

Fig. 3. Dense microstructure of the four CSAM Cu de- posits.

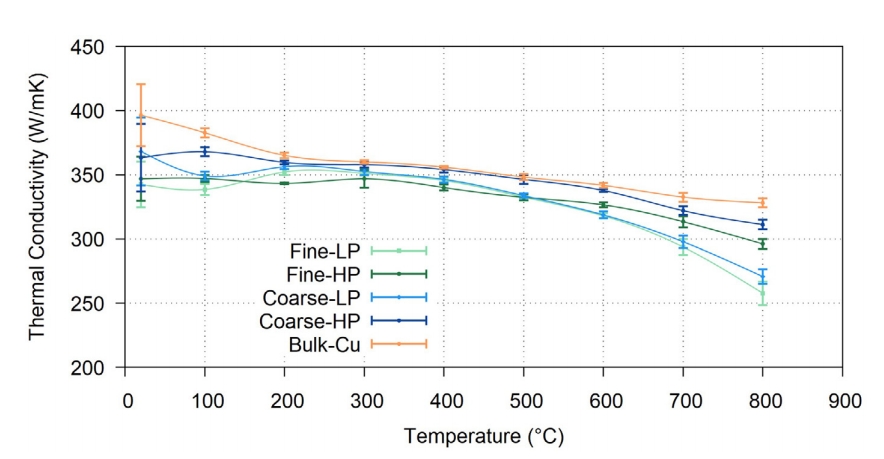

Fig. 4. Thermal conductivity of the four CSAM Cu de- posits and bulk Cu.

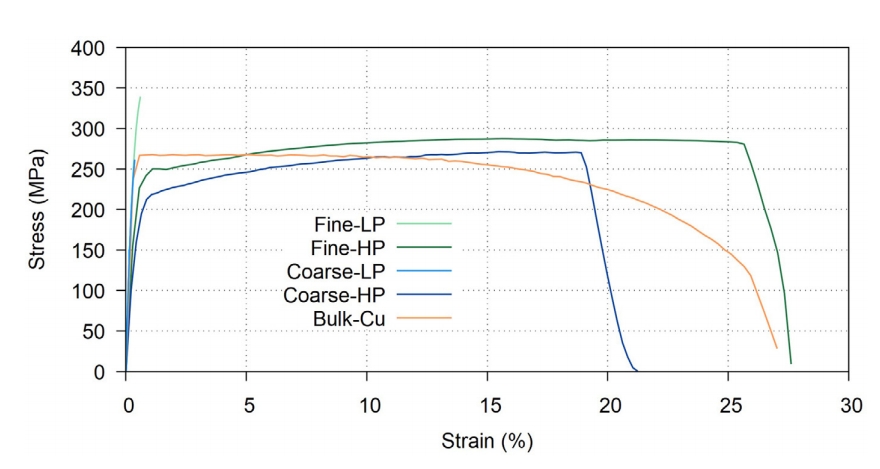

Fig. 5. Stress-strain curves showing high strength and ductility of cold sprayed Cu deposited at high process parameters, fully comparable to those of bulk Cu.

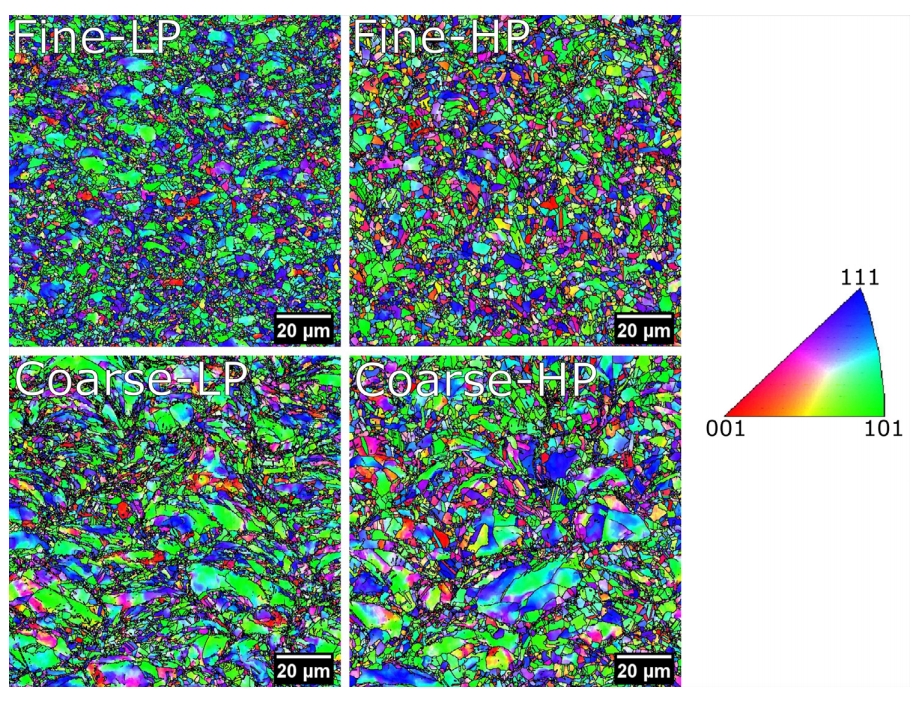

Fig. 6. EBSD IPF maps of the cold sprayed Cu deposits microstructure showing bimodal grain distribution.

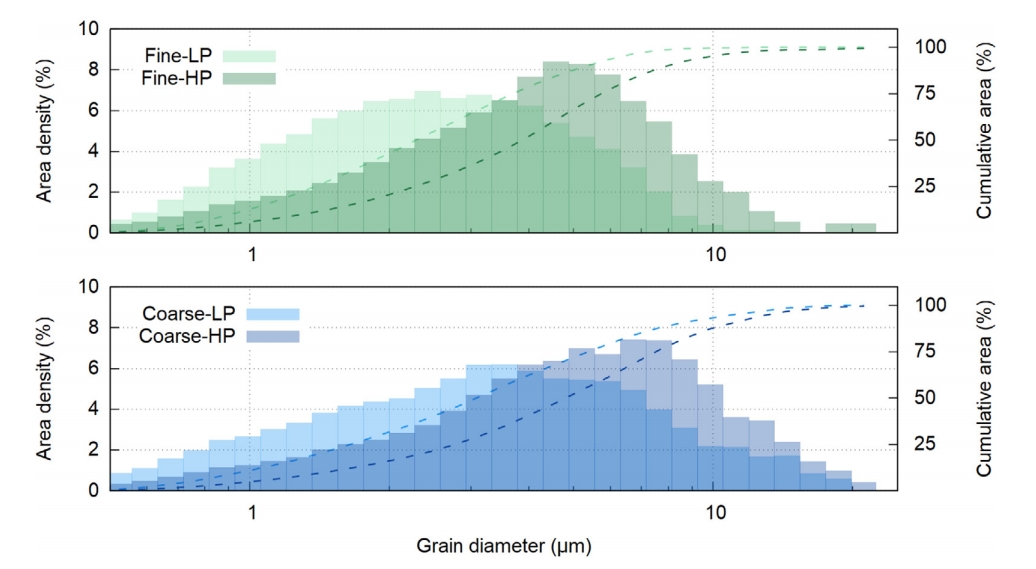

Fig. 7. Area grain size distribution in CSAM Cu deposits.

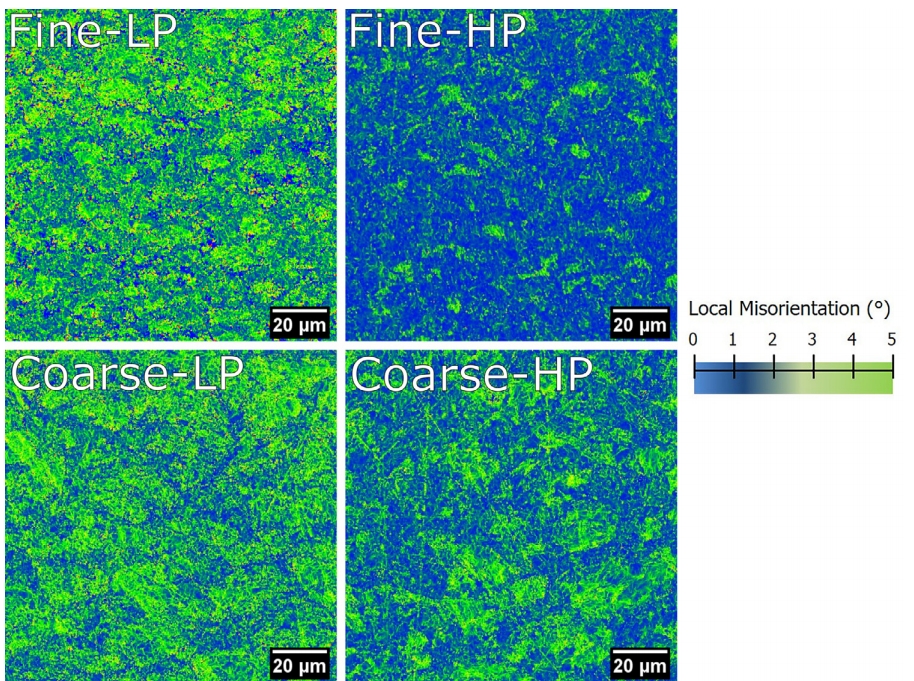

Fig. 8. Local grain misorientation maps of the cold sprayed Cu showing the amount of local- ized plasticstrain.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Microstructure and thermal properties

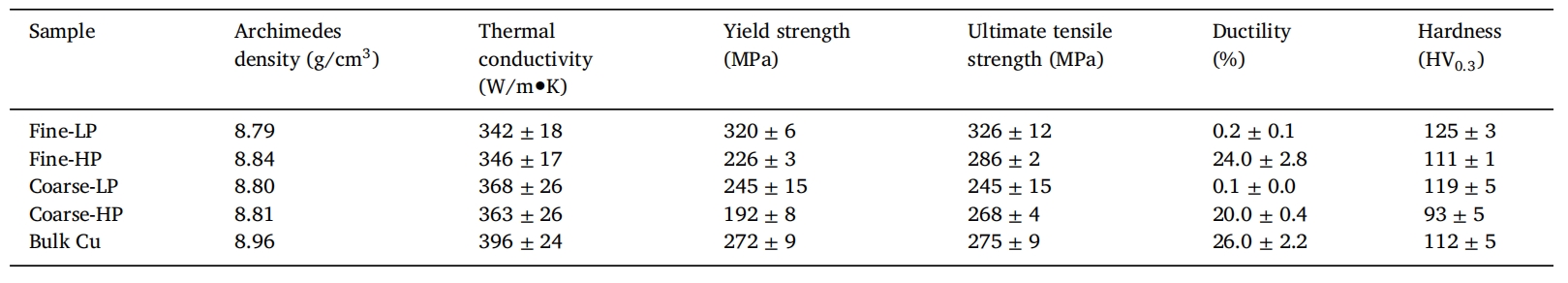

The SEM BSE micrographs shown in Figure 33 demonstrate a very dense microstructure of the materials deposited from both powders at low and high parameters. In fact, the densities of Cu deposits deter- mined by the Archimedean immersion method (Table 2) correspond to porosities lower than 1.5%, i.e., values comparable to bulk, metallurgi- cal Cu. To assess the density further, a gas tightness test of the dense Cu deposits was carried out using He leak detection. In all deposits, a He ?owrate smaller than 1 × 10?7 mbar?l/s was observed. According to [20, 21], the values below 1 × 10?7 mbar?l/s are considered a very tight system. In other words, the test con?rmed that the cold sprayed deposits are very dense, and the limited porosity in the Cu-deposits is not interconnected.

The achieved density values standout even more if compared against the Cu manufactured by other AM processes. For instance, Lykov et al. (2016) achieved 88.1% density in Cu produced by selective laser melting process [22], while Kumar etal. (2019) measured 77% to 97% density in sintered and HIPed Cu produced by binder jetting additive manufac- turing [23].

Thermal conductivity of the Cu deposits was recorded in the tem- perature range of 20–800 °C, as shown in Fig. 4. It can be observed that the thermal conductivity of all samples is comparable to the bulk Cu counterpart, indirectly con?rming the deposits quality. The slightly better values of both HP deposits (pronounced at higher temperatures) likely stem from their slightly better density and di?erent microstruc- ture topology (discussed in Section 3.2.1). It can also be observed that the coarse powder deposits demonstrated a slightly higher thermal con- ductivity than the ?ner powder deposits, a trend similar at both pro- cess parameters. This could, again, becaused by the speci?c microstruc- ture topology. For all samples, the thermal conductivity decreases with increasing temperature. In metals, this is a well-known phenomenon as their thermal conductivity mostly depends on the ?ow of electrons, which is hindered by lattice vibrations at increased temperatures [24, 25].

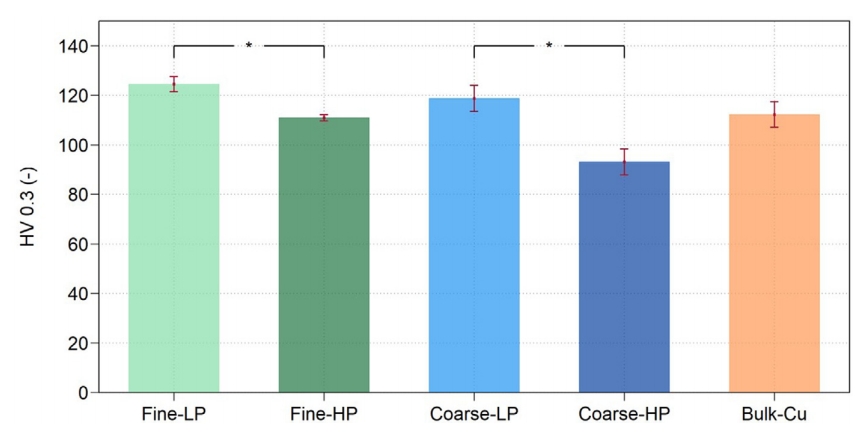

Fig. 9. Vickers HV0.3 hardness of the four CSAM Cu deposits and bulk Cu. Asterisk denotes a signi?cantsta- tisticaldi?erence between the mean values at a con?- dence level of p = 0.01.

Table 2

Properties of cold sprayed Cu-deposits in comparison to bulk-Cu at room temperature.

3.2. Mechanical properties

3.2.1. Tensile strength and ductility

The representative stress-strain curves are shown inFig. 5. These re- sults show that at LP, both cold sprayed deposits exhibit a high tensile strength accompanied by a very low ductility. Such properties are typ- ical for the as-deposited CSAM materials and are a consequence of the extreme work hardening during the plastic deformation of the powder particles. The game-changing results are the curves obtained for Cu sam- ples deposited at HP. These are characterized by high tensile strength as well as high ductility, both fully comparable to the bulk (i.e., non- AM) counterpart. Developing an AM material with a simultaneous high strength and high ductility has always been a challenging task, in par- ticular since strength and ductility are usually mutually exclusive. To the best of our knowledge, such a result for cold sprayed Cu in the as- sprayed state has not been reported previously.

The tensile test data further suggest that the Cu deposits sprayed at both process parameters using the ?ner powder show higher strength when compared to their counterparts sprayed from the coarser feed- stock. This e?ect is, however, less signi?cant than the in?uence of the process parameters.

![]() Grain re?nement from coarse grains down to ultra?ne and further to nanoscale grains is a well-known approach to strengthen metallic mate- rials [26,27]. The penalty in this approach is usually a poor ductility due to the limited capacity to store dislocations that results in an early strain localization during mechanical loading. To overcome this, fabrication of bimodal grain size microstructure has been proven as a strategy to en- hance the ductility in ultra?ne grain materials, at a little sacri?ce in tensile strength. In materials with such bimodal grain size distribution, the ultra?ne grains provide high strength, whereas the coarse grains work as sinks for dislocations storage and enhance the ductility [28– 31]. The tensile test data suggested that at HP, the Cu deposits could possess such bimodal microstructure, providing them with high strength and ductility. To investigate this hypothesis and also to detect the po- tential microstructure recrystallization, EBSD inverse pole ?gures (IPF) and local grain misorientation (KAM) maps of all four CSAM deposits were acquired.

Grain re?nement from coarse grains down to ultra?ne and further to nanoscale grains is a well-known approach to strengthen metallic mate- rials [26,27]. The penalty in this approach is usually a poor ductility due to the limited capacity to store dislocations that results in an early strain localization during mechanical loading. To overcome this, fabrication of bimodal grain size microstructure has been proven as a strategy to en- hance the ductility in ultra?ne grain materials, at a little sacri?ce in tensile strength. In materials with such bimodal grain size distribution, the ultra?ne grains provide high strength, whereas the coarse grains work as sinks for dislocations storage and enhance the ductility [28– 31]. The tensile test data suggested that at HP, the Cu deposits could possess such bimodal microstructure, providing them with high strength and ductility. To investigate this hypothesis and also to detect the po- tential microstructure recrystallization, EBSD inverse pole ?gures (IPF) and local grain misorientation (KAM) maps of all four CSAM deposits were acquired.

The IPF maps presented in Figure 66 clearly show a speci?c mi- crostructure where coarse grain areas located in the center of the origi- nal Cuparticles are enclosed in a continuous network of few micrometer- sized ultra-?ne grains along the particles’ rims. The IPF maps of Fine- LP (particle velocity 688 m/s) and Fine-HP (particle velocity 813 m/s) deposits show a clearly visible bimodal structure formed at both pro- cess parameters. However, at LP, the spatial topological distribution of the coarse grains and ?ne grains is not homogenous, with some areas showing only the ?ne grains, and the ultra?ne grains network is fur- ther not homogeneously distributed. Contrary to LP, the microstructure of the Fine-HP deposits demonstrates a homogeneous spatial topologi- cal distribution of the coarse and the ?ne grains, with coarse grain areas regularly surrounded by the interconnected ultra?ne grains network. As discovered in other studies (e.g., Zhang et al. for 304 L stainless steel [32]), the spatial topological distribution (discussed for our deposits) is another factor that plays a major role in achieving the simultaneous high ductility and high strength at HP. A similar behavior was observed in the microstructure of the coarse Cu powder deposits at LP and HP: the microstructure of Coarse-LP (particle velocity 591 m/s) illustrates a non- homogeneously distributed elongated big grains, along with irregular and relatively thicker ultra?ne grains network, while Coarse-HP (par- ticle velocity 662 m/s) shows more homogeneously distributed coarse grain areas surrounded by relatively thinner ultra?ne grain walls. In all deposits the elongated coarse grains observed in the microstructure could appear because of the jetting phenomenon during the powder par- ticle impact, as also reported by Borchers et al. [33] and Rahmati et al.

From the EBSD results, it is clear that all four deposits exhibit a bi- modal structure, but they di?erin the ratio of ?ne and coarse grains. To quantify the di?erence, the EBSD IPF maps were used to calculate the area-weighted grain size distribution within each deposit (Fig. 7). The histograms clearly show that the process parameters (LP vs. HP) signif- icantly in?uence the grain size distribution. For both types of feedstock powder, the deposits sprayed at HP show a higher proportion of larger grains. Such shift is triggered by the discussed grain recrystallization and gives rise to a microstructure composed of ?ne and coarse grains alike. In terms of absolute values, the median grain sizes shifted from 2.3 μm to 3.9 μm and from 3.1 μm to 4.8 μm for the ?ne and the coarse powders, respectively. Furthermore, unlike the in?uence of process pa- rameters, there is no signi?cant di?erence between the two powders under LP and HP.

To further understand the microstructure formation, local grain mis- orientation (KAM) maps were calculated from the IPF maps, revealing the amount of plastic strain in the deposits (Fig. 8). The results sug- gest that both deposits sprayed at LP exhibit a highly strained interior of the coarse grains as well as the grain boundaries. It can also be ob- served that the proportion of non-indexed area (mostly limited to parti- cle boundaries and at the coarse-?ne grains interface regions) is higher in the Fine-LP, indicating either a highly deformed region with high dis- location density or very small nanocrystalline features below the EBSD resolution limits. The misorientation maps of both HP deposits show a less strained area and almost no non-indexed area compared to the maps of LP.

Combined, the EBSD results indicate that although the plasticstrain still exists, thermal softening and recrystallization were dominating the shearstraining caused by the very high particle impact velocities. It has also been reported in the literature that in the case of copper, parti- cle velocities exceeding 600 m/s are su?cient to increase the localized temperature close to the melting point,i.e., high enough for a dynamic recrystallization in the highly strained material [33–35]. The particle velocities achieved in our study at both LP and HP are su?cient to trig- ger this process for both powders.

In the previous studies {e.g., [33]}, it has been proposed that mi- crostructure evolution during a dynamic recrystallization for high strain rate deformation occurs in ?ve stages: (i) random distribution of dislo- cations, (ii) dynamic recovery by the formation of elongated dislocation cells, (iii) elongated dislocation cells arrangement to form elongated sub-grains, (iv) break-up of the elongated sub-grains, and (v) forma- tionofrecrystallized microstructure with small equiaxed grains. As also reported by Borchers et al. (2003) and Schmidt et al. (2006), a higher particle velocity produces a higher localized temperature rise, which then provides more time for the microstructure evolution [33,36].

The results presented in the current study suggest that at LP, the el- evated temperature conditions exist for an insu?cient amount of time only, and, therefore, the recrystallization cannot fully evolve. Instead, the microstructure development ceases at the early stage, and, as a result, the observed highly strained and heterogeneous bimodal mi- crostructure is formed. This a?ects the mechanical properties of the CSAM Cu deposits, displaying the high strength but very low ductility. Contrary to this, at HP, the higher particle velocities of both powders in- duce higher temperatures, thereby facilitating dynamic recrystallization and stimulating a fully evolved bimodal microstructure with relaxed grains. The results further indicate a homogenous and relaxed bimodal microstructure where the coarse grain areas are surrounded by a con- tinuous network of ultra?ne grains is required to obtain the synergistic e?ect of simultaneous high strength and high ductility. In our study, this was observed for both powders sprayed at HP. The bimodal microstruc- ture in the cold sprayed Cu was also reported earlier by Jakupi et al. (2015) [35]. However, the bimodal structures presented there showed heterogeneity in the spatial topological distribution of both the coarse grain areas and the ultra?ne grains network, and, as a result, the ob- served high strength was accompanied by a very low ductility, similar to our results at LP.

3.2.2. Hardness

Fig. 9 demonstrates the in?uence of the powder particle size and the process parameters on hardness of the CSAM Cu deposits. The hard- ness follows the trend observed for the tensile strength behavior (Fig. 5), i.e., the ?ne powder deposits show higher values due to their ?ner grain structure (shown in Figure 66). The ?ne-grain microstructure contains a high density of grain boundaries, which act as obstacles for disloca- tion motion,resulting in dislocations pileups in the regions close to the grain boundaries during the indentation. Consequently, a higher stress is required to move the dislocations through these pileups, resulting in an increase in hardness [37].

At the used process parameters, the di?erence in the hardness values of the ?ne and coarse powder deposits is not very signi?cant, though. As opposed to this, the e?ect of the process parameters is manifested nicely. The statistical analysis by a two-tailed t-test indicates a signi?cant dif- ference between the mean values (p < 0.01) of hardnesses ofthe samples deposited at LP and HP. Apparently, as discussed in Section 3.2.1, at LP, the shearstraining dominates over recrystallization, while at HP, a fully recrystallized and relaxed microstructure was obtained. As a result, the hardness decreases for both HP deposits. The very low standard devi- ations suggest that all four CSAM Cu deposits are very homogenous in terms of their macro-properties. Last, the cold sprayed Cu deposits have a hardness comparable to bulk Cu.

4. Conclusions

Pure copper CSAM deposits have been produced using spherical pow- ders, a high-pressure gun, and nitrogen as a process gas. The in?uence of process parameters and powder particle size has been investigated. From the results, the following conclusions can be drawn:

? Almost pore-less Cu deposits (density of 8.79–8.84 g/cm3, fully suppressing helium leak) can be produced by CSAM, having a high thermal conductivity of 368 W/m?K comparable to bulk Cu (396 W/m?K) in their as-sprayed state.

? Without any secondary processing (such as heat treatment), a si- multaneous high strength and high ductility can be achieved in the deposits at high spray parameters, regardless of the used Cu powder. This is provided by the favorable topology of the bimodal microstruc- ture, consisting of coarse grains enclosed in a network of ?ne grains along the individual particle rims.

? The process gas parameters (temperature and pressure) have a more signi?cant in?uence on the mechanical properties than the used feedstock average particle size. A combination of the ultimate tensile strength of 286 MPa and 24% ductility was achieved in CSAM Cu.

The thermo-mechanical properties of the CSAM Cu deposits devel- oped in our work are fully comparable to bulk Cu produced by a non- additive metallurgy method. Considering the high deposition e?ciency (99%) and high deposition rates, this letter illustrates a huge potential of the method to be implemented in various industrial sectors for either demanding applications or even in serial production.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing ?nancial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to in?uence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

Authors greatly acknowledge Mr. Stefan Heinz, Dr. Georg Mauer, and Dr. Stefan Baumann, Institute of Energy and Climate Research, Material Synthesis and Processing (IEK-1), Forschungszentrum Jülich, Germany, for performing the He-leak tests in the cold sprayed cop- per samples. Authors would also like to thank Mr. Lukas Loidl for his support in cold spraying and Mr. Maximilian Meinicke’s sup- port in project management. This work was funded by Impact In- novations GmbH, Germany. Part of the sample characterization was funded by COMTES FHT a.s. within the project "Pre-Application Re- search of Functionally Graduated Materials by Additive Technologies, No.